How Many Babies Died From Sids in 2018

- Enquiry article

- Open Access

- Published:

International time trends in sudden unexpected babe death, 1969–2012

BMC Pediatrics volume twenty, Article number:377 (2020) Cite this article

Abstruse

Background

Sudden unexpected baby death (SUID) - including sudden infant expiry syndrome (SIDS) - continues to be a major contributor to infant bloodshed worldwide. Our objective was to analyse time trends and to identify country-clusters.

Methods

The National Statistical Offices of 52 countries provided the number of deaths and live births (1969–2012). Nosotros calculated infant mortality rates per yard live births for SUID, SIDS, and all-cause mortality. Overall, 29 countries provided sufficient data for time course analyses of SUID. To sensitively model modify over time, we smoothed the curves of mortality rates (1980–2010). We performed a hierarchical cluster analysis to identify clusters of fourth dimension trends for SUID and SIDS, including all-crusade infant mortality.

Results

All-cause baby mortality declined from 28.5 to 4.eight per thousand live births (mean 12.4; 95% conviction interval 12.0–12.9) betwixt 1969 and 2012. The cluster assay revealed four country-clusters. Clusters 1 and 2 mostly contained countries showing the typical peak of SUID bloodshed during the 1980s. Cluster i had higher SUID mortality compared to cluster 2. All-crusade baby mortality was low in both clusters just higher in cluster one compared to cluster 2. Clusters three and iv had low rates of SUID without a elevation during the 1980s. Cluster 3 had the highest all-cause babe mortality of all clusters. Cluster four had an intermediate all-cause baby mortality. The time trends of SUID and SIDS mortality were similar.

Conclusions

The country-specific fourth dimension trends in SUID varied considerably. The identification of state-clusters may promote enquiry into how changes in slumber position, smoking, immunisation, or other factors are related to our findings.

Background

Mortality from sudden baby death syndrome (SIDS) is still a major contributor to mortality in the first year of life worldwide [1]. In many Western countries, including Western Europe, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States, bloodshed from SIDS peaked in the 1980s and decreased during the 1990s [ii,3,4,5,six]. In other countries, such as Japan, SIDS mortality was depression during the 1980s and afterwards increased [7, viii]. The decrease in SIDS mortality in Western countries has been attributed mainly to the 'Back to Sleep' campaigns promoting the supine sleep position [ii, three, nine]. In the United states of america, for instance, the National Infant Sleep Position Study showed an increase in the supine slumber position from 17% in 1993 to 72% in 2007 [10].

Gilbert et al. assessed the time frame for 'Back-to-Slumber' campaigns in diverse countries in a systematic review [9]. The campaigns frequently coincided with reductions in SIDS. The International Child Care Practice Report, however, found large variations in babe sleep position betwixt countries [eleven]. For instance, the prevalence of the supine sleep position was 33% in Denmark compared to 89% in Nippon in the late 1990s. While baby slumber position and other take chances factors act as triggering factors, the underlying cause(due south) for SIDS are withal unknown [12]. The success of the 'Dorsum-to-Slumber' campaigns might accept covered concurrent changes in other factors at the population level. Known take a chance factors for SIDS other than the prone or side sleep position include bed sharing, soft bedding, mothers' smoking and booze use, overheating, and lack of immunisation [4, 12, 13].

Determining regional fourth dimension trends for SIDS mortality and identifying clusters of time courses might instigate new research into the aetiology of SIDS. As the coding of SIDS varies between countries, the broader category of sudden unexpected infant death may be more advisable for international comparisons [14]. The term sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI) is often used interchangeably with SUID as an umbrella term for unexplained infant deaths [15]. During recent years, diagnostic shifts take been reported from SIDS to other diagnoses [16, 17]. Sudden unexpected infant expiry (SUID) typically includes SIDS, accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed, or other ill-defined or unspecified causes of decease [xiii]. When comparing SUID mortality, all-cause infant mortality needs to be taken into account also. In countries with high all-cause infant bloodshed, vulnerable infants might die earlier from other causes. Therefore, the objective of the present study was to identify country-clusters with similar time trends in SUID and SIDS as well as in all-crusade baby bloodshed in an international comparison.

Methods

Study pattern

The present report is a comparing of historical time trends in SUID, SIDS, and all-crusade infant mortality between countries across the earth (1969–2012). Infant deaths were divers as deaths in children during the first year of life. We obtained data from the National Statistical Offices of the respective countries. In the case of missing data, we checked the Globe Wellness Organization (WHO) Mortality Database and included additional information if bachelor [18]. Diagnoses were used according to the International Nomenclature of Diseases (ICD) systems [nineteen]. Our primary diagnosis of interest was SUID. The diagnosis of SUID commonly includes SIDS (ICD-10, R95), accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed (ICD10, W75), or other ill-defined or unspecified causes of mortality (ICD-ten, R99) [14, 16]. We used the broader category ill-defined and unknown causes of mortality (ICD-ten, R96–99), equally international comparisons have shown differences in the use of private codes of diagnoses between countries [14]. For example, a loftier percentage of SUID was coded every bit other sudden death, cause unknown (ICD-10, R96) in Japan [14]. Codes of diagnoses used for SUID and related diagnoses might differ both between and inside countries over fourth dimension. During the period of interest, the ICD systems changed [19]. We used the post-obit ICD systems: the eighth revision (ICD-8), the ninth revision (ICD-9), and the 10th revision (ICD-10) (Tabular array 1). The years in which ICD systems changed differed betwixt countries.

A number of countries used other classification systems, such equally the 09 N – ICD 9th revision, Special List of causes (tabulation list) (countries of the sometime Matrimony of Soviet Socialist Republics, USSR), the 09A/09B – List ICD 9th revision, Standard Basic Tabulation (Croatia, Greece, Iceland, Japan, New Zealand), or the Finnish Classification of Diseases 1987. The High german Democratic Republic (German democratic republic), which existed until 1990, used a special version of the ICD for the coding of deaths. For the latest years of our report, all countries - apart from Greece - had adopted the ICD-x codes. The causes of death in Greece were coded with ICD-nine until 2013.

Regions and countries

For the nomenclature of regions, we used geographic units that were adapted from the Global Burden of Disease Report [ane]. We included the following regions and countries of interest in our written report, focusing on Europe, with selected countries from other regions of the globe for comparisons:

- 1)

Western Europe (Austria, Belgium, Cyprus, Kingdom of denmark, East Germany, England & Wales, Finland, France, Greece, Iceland, Republic of ireland, Italian republic, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Northern Ireland, Norway, Portugal, Scotland, Espana, Sweden, Switzerland, West Federal republic of germany) excluding Andorra, Liechtenstein, Monaco, and San Marino due to the minor population sizes (≤90,000 inhabitants). We did not provide a total estimate for the United Kingdom due to the differential use of ICD systems. Similarly, we included Due east and Westward Frg separately due to differences in coding and classification systems used over time.

- 2)

Central Europe (Albania, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Democracy, Hungary, Kosovo, Macedonia, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia).

- 3)

Eastern Europe (Republic of belarus, Republic of estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Republic of Moldova, the Russian federation, Ukraine).

- 4)

Selected countries from other regions: high-income N America (Canada, U.s.), Australia (Commonwealth of australia, New Zealand), high-income Asia Pacific (Nippon), Southern Latin America (Chile, Uruguay), Central Latin America (Republic of costa rica, United mexican states), and North Africa and Center East (Turkey).

Fourth dimension period and data collection

We used all data on infant mortality with the respective codes of diagnoses for the time period from 1969 to 2012 for the descriptive analyses [20]. For the cluster analyses of fourth dimension trends, we restricted the time period to the years from 1980 to 2010 due to the large corporeality of missing data for the earlier and later years. We included 29 countries for the cluster analyses of time trends in SUID mortality and 27 countries for SIDS bloodshed, respectively.

The format (paper-based, digital) and degree of segregation of the data varied considerably between countries. Some countries just provided aggregated information for the ICD category symptoms, signs and aberrant clinical and laboratory findings, not elsewhere classified (ICD-10, R00-R99) but not separately for the diagnoses SIDS (ICD-10, R95), accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed (ICD-x, W75), or ill-defined and unknown causes of mortality (ICD-10, R96–99).

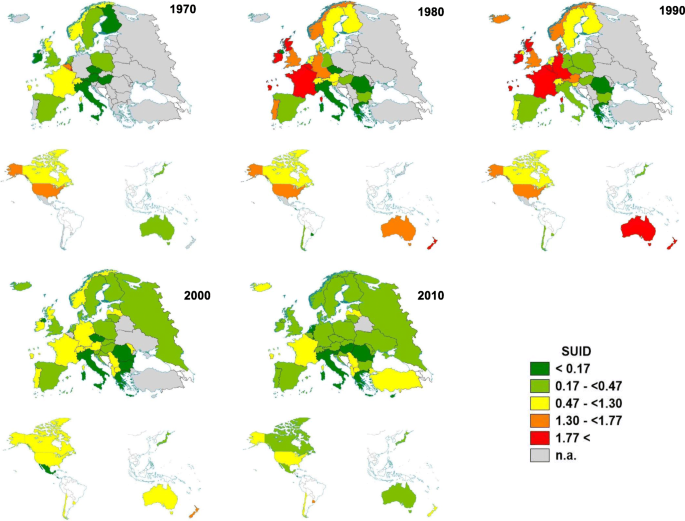

Statistical analyses

We calculated babe mortality rates per chiliad past dividing the number of infant deaths with the corresponding diagnoses by the number of live births multiplied by 1000. For the descriptive analyses, we divided mortality rates from SUID bloodshed into quintiles over 3-twelvemonth periods. We calculated the distribution over these quintiles with 1980–1982 equally the reference years for both previous and subsequent years. We used maps to display the distribution of SUID mortality rates graphically for the years 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010. To create the maps, we used the software EASYMAP 11.0 SP 6 (@2018 Luttum+ Tappert DV-Beratung GmbH, Bonn, www.lutumtappert.de).

Mortality rates from SUID can be affected by all-cause mortality rates. Therefore, we examined the time trends of mortality rates from SUID, SIDS, and decease from all-causes. The time series of mortality rates were smoothed before further assay using restricted cubic splines with half dozen nodes. Smoothing data removed dissonance from the data and allowed u.s. to sensitively model changes over time. We performed hierarchical cluster analyses to place similar time courses of SUID and SIDS across countries. Countries were clustered for SUID and all-cause bloodshed every bit well equally for SIDS and all-cause infant mortality. We used the values of the smoothed SUID, SIDS, and all-crusade infant mortality curves from 1980 to 2010 for the cluster analyses. In total, 62 variables were the basis for each of the two cluster analyses. Because the higher levels of all-crusade baby bloodshed would give all-cause infant mortality a greater weight in the cluster analyses, we calculated Manhattan altitude matrices for SUID and all-cause mortality separately and averaged both altitude matrices. Thus, we were able to ensure equal weight of SUID and all-cause mortality in the cluster analysis. The altitude matrix for clustering SIDS mortality was calculated appropriately. Finally, the hierarchical cluster algorithm used Ward's minimum variance method. Nosotros calculated country-specific maxima over time based on the smoothed curves for the mortality rates from SUID and SIDS. For the calculation of the restricted cubic splines, we used the R package "rms". The cluster analyses were carried out using the hclust function from the statistical software R iii.iii.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Calculating, Vienna).

Results

In full, 52 countries provided information on infant mortality. All-cause babe mortality decreased from an boilerplate of 28.5 per 1000 live births in 1969 to 4.8 in 2012 (mean bloodshed rate over all years: 12.four; 95% conviction interval 12.0–12.9). While all-crusade baby bloodshed rates were bachelor for all countries from 1969 to 2012, the completeness of available mortality information to calculate SUID mortality was initially low; still, it improved during the fourth dimension menses of interest. Data on SUID were available for 22 countries in 1970, 32 in 1980, 35 in 1990, 45 in 2000, and 49 in 2010. Bloodshed from SUID declined in most regions. Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of SUID mortality rates for the years 1970, 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010.

Regional distribution of infant bloodshed rates from sudden unexpected infant decease (SUID) per m live births in 10-twelvemonth intervals; meridian: Europe, bottom left: Americas, bottom correct: Australia, Japan, New Zealand

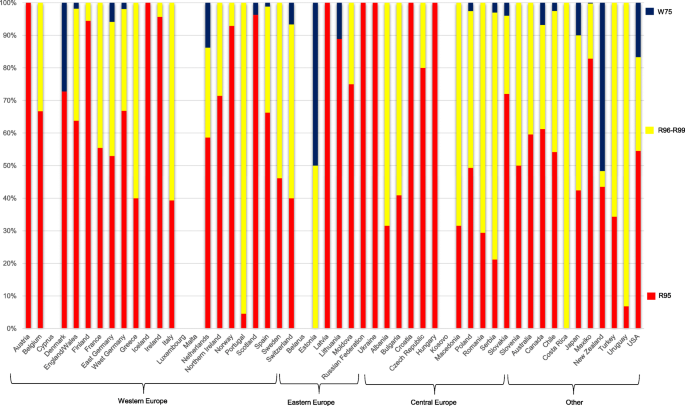

Differences existed in the employ of codes of diagnoses between countries. The percentage of SIDS mortality among SUID mortality ranged between 30 and 40% from 1969 to 1976, rose steadily to 83% in 1994, and declined once again, ranging betwixt threescore and 70% from 1995 onwards. In 1970, for example, Republic of austria, Finland and France did not code whatsoever cases of SUID as SIDS, whereas the Czech Republic, Luxembourg, and Poland coded all SUID cases as SIDS. Differences persisted over fourth dimension. In 2010, only a low per centum of SUID cases was coded as SIDS in Costa rica and Estonia (both 0%) and Portugal (v%), whereas Austria, Croatia, Republic of hungary, Iceland, Latvia, the Russian Federation, and Ukraine coded all SUID as SIDS. Figure ii shows the distribution of the corresponding diagnoses amid SUID bloodshed rates according to country (year 2010). The distribution of diagnoses over time for the preceding decades (1980, 1990, 2000) is shown in the Additional file 1.

Distribution of sudden unexpected infant death by its component diagnoses, co-ordinate to country (2010); SIDS (ICD-10, R95), ill-defined and unknown causes of mortality (ICD-x, R96–99), accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed (ICD10, W75)

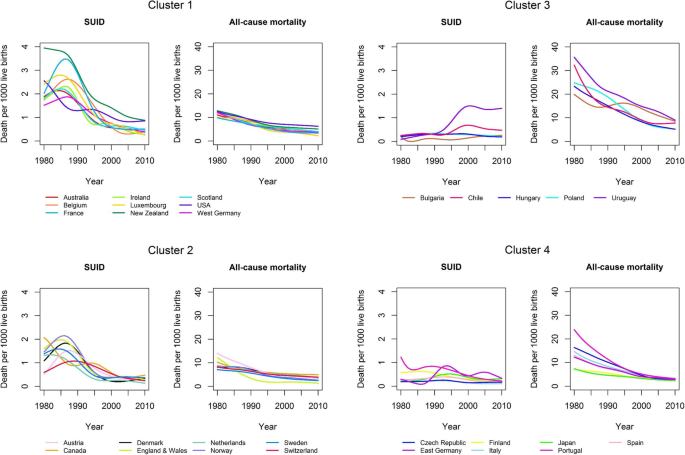

Fourth dimension trends for SUID mortality rates from 29 countries were grouped into four clusters (Fig. 3, Table two). Table 2 shows the maxima of SUID mortality per country-cluster, based on smoothed curves. The main departure between cluster one and cluster 2 countries with regard to SUID were the lower SUID and all-cause mortality rates in cluster 2. The maximum of SUID rates was 3.ix per 1000 live births (New Zealand) with the lowest value of 1.nine for West Germany in cluster 1, the maximum of SUID rates in cluster 2 was 2.2 (Norway) with the lowest value of 1.1 for Switzerland. With regard to the dynamic, SUID rates decreased from around ii.1 in 1990 to 1.one in 1995 in cluster 1, while they decreased from effectually one.3 to 0.half dozen during the aforementioned time catamenia in cluster ii. Cluster 1 included mainly countries from Western Europe (Belgium, France, Republic of ireland, Grand duchy of luxembourg, Scotland, West Germany) as well as Australia, New Zealand and the USA. Cluster 2 included Austria, Canada, Denmark, England & Wales, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland. In cluster three (Bulgaria, Chile, Republic of hungary, Poland, Uruguay), mortality rates from SUID were low, while all-crusade infant bloodshed was approximately ii-fold higher compared to clusters 1 and 2. Mortality rates from SUID remained beneath i (except for Uruguay in 2001). Cluster iv (Czech republic, East Germany, Finland, Italia, Japan, Portugal, Spain), similarly, had low bloodshed rates from SUID. All-cause infant mortality rates were lower in cluster 4 compared to cluster 3.

Land-clusters of sudden unexpected infant expiry (SUID) and all-crusade babe mortality (1980–2010)

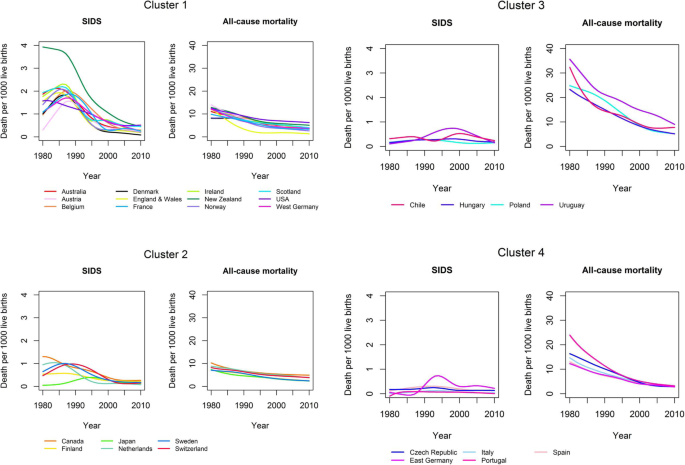

Time trends for SIDS mortality rates from 27 countries were grouped into 4 clusters (Fig. 4, Tabular array three). Table three shows the maxima of SIDS mortality per country-cluster, based on smoothed curves. The differences between clusters ane and 2 in the cluster analysis of SIDS were similar to those of SUID (Table ii, Table 3). Almost of the countries were in the same clusters (Cluster 1: Australia, Kingdom of belgium, France, Ireland, New Zealand, Scotland, USA, West Germany; Cluster 2: Canada, Sweden, Switzerland, the Netherlands) in both analyses. Some of the countries could only be analysed with regard to one of the outcomes SIDS or SUID (Luxemburg, Finland, Japan). In four countries, the cluster allocation was different for SIDS compared to SUID: Republic of austria, Denmark, England & Wales and Norway. All four were in cluster one for SIDS but in cluster 2 for SUID. For these countries, rates of SIDS and SUID were almost identical and rates of SIDS were higher than in countries of cluster 2 (SIDS). When analysing SUID rates in these countries, they were lower than in other countries of cluster 1. Cluster i included 12 countries predominantly from Western Europe likewise every bit Australia, New Zealand and the USA. A top of SIDS mortality was reported between 1980 and 1988 (range: 1.6–iii.nine). Following the peak in bloodshed, SIDS mortality rates decreased until 2010. New Zealand had the highest SIDS bloodshed of all countries. All-crusade infant bloodshed in cluster one was between 7 and 15 and decreased continuously from 1980 onwards. Countries of cluster 2 (Canada, Republic of finland, Nippon, Netherlands, Sweden, Switzerland) showed similar trends in SIDS mortality compared to cluster 1 just at a lower level. A maximum of SIDS mortality was reported between 1980 and 1995 (range: 0.4–ane.iii). Clusters 3 (Chile, Republic of hungary, Poland, Uruguay) and iv (Czech republic, Due east Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain) had low SIDS mortality rates (beneath 1) but differed with regard to all-cause infant mortality. Cluster 3 had the highest all-cause baby mortality of all clusters, while cluster 4 had intermediate infant all-mortality.

Country-clusters of sudden babe decease syndrome (SIDS) and all-cause babe bloodshed (1980–2010)

Give-and-take

All-cause infant mortality besides as SUID and SIDS bloodshed declined in almost countries. The cluster analyses yielded 4 country-clusters for both SUID and SIDS. Two of the clusters showed the typical top in SUID and SIDS mortality observed during the 1980s, mainly in countries from Western Europe too as Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the Usa. These clusters had a depression all-cause infant bloodshed but differed with regard to their levels of SUID and SIDS mortality. The remaining ii clusters had high and intermediate all-cause infant mortality, with low mortality from SUID and SIDS. These clusters predominantly included countries from Central Europe too as some countries from the Mediterranean region.

Most studies comparison international time trends take focused on SIDS but not SUID mortality [ane, 2]. Coding practices for SIDS and SIDS-related diagnoses, yet, vary considerably between countries [14]. In Japan, for case, just approximately 40% of SUID cases are coded as SIDS [fourteen]. Whereas the R96 diagnosis (other sudden death, cause unknown) is predominantly used equally an alternative to SIDS in Nippon, other countries, such equally Canada, England & Wales, Deutschland, or the U.s., are more probable to use the lawmaking R99 (other ill-defined and unspecified causes of mortality) or W75 (accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed). Comparison time trends in SUID thus allows for a more robust comparison between countries and over time. We as well included all-cause infant bloodshed in our cluster analyses. The low SUID mortality plant in the clusters with loftier and intermediate all-cause infant mortality may at least partially be due to vulnerable children dying earlier from other causes. In particular, mortality from perinatal conditions was increased in the countries with high and intermediate all-cause mortality, too equally mortality from infections in countries with high all-crusade bloodshed [18].

The initial increase and subsequent decrease in SIDS mortality in many countries has been attributed to changes in infant sleep position [iii, five, ix]. Campaigns promoting the supine sleep position started in most countries during the early 1990s [9]. While the change in infant slumber position is a major cistron associated with reducing SIDS mortality, other changes in potential adventure factors at the population level take received less attention. For example, immunisation against pertussis decreased in a number of countries during the 1980s due to reports of neurological complications [21]. In countries such every bit the United Kingdom, West Germany, or the The states, the uptake of pertussis immunisation only recovered in the belatedly 1980s and early 1990s [4, 21]. Immunisation was establish to exist associated with a reduced hazard of SIDS in case-control and cohort studies [22, 23]. Reductions in other risk factors for SIDS, such as smoking, could also exist observed at the population level [24]. Many risk factors for SIDS are associated with socioeconomic status and tend to cluster in high-risk populations [12, 25, 26].

Limitations

1 limitation of our study was the missing data on SUID and SIDS for certain periods of time in a number of countries. Another limitation is that some of the observed differences may have been caused by artefacts as definitions of SIDS as well as diagnostic procedures varied between countries and over fourth dimension [2, 27]. The definition of SIDS has changed since its original implementation in 1969, with a stronger focus on death scene investigation including a complete autopsy as requirement for the diagnosis [28]. An increasing reluctance by decease certifiers to diagnose SIDS without a thorough investigation might take led to the increment in other diagnoses, as observed in the The states [17]. To our knowledge, there is no systematic cess of international autopsy rates in infants dying from SIDS in countries over time. In a study comparing eight countries, the estimated percentage of SIDS cases being autopsied differed largely between countries with, for example, specially low autopsy rates reported for Nihon and the Netherlands [14, sixteen]. The low autopsy charge per unit in Japan might be associated with the observed higher rate of the diagnoses ill-defined and unknown causes of mortality. The comprehensiveness of the dissection protocol may vary between countries [29]. Oft, no systematic information is available on whether an autopsy and/or expiry-scene investigation was performed co-ordinate to standard protocols [16]. In general, decease certifiers and pathologists may individually or regionally be more likely to over- or underdiagnose SIDS [xvi]. The age of inclusion as SIDS differed between countries [two]. Some countries defined SIDS as death from 1 week to 12 months, while others used birth to 12 months or across. As the majority of SIDS occurs between two and iv months, the outcome is likely to be minor [12, 30]. The definition of live births similarly varied between countries [8]. Even so, most countries adopted the standard definition of the WHO in the late 1980s or early on 1990s [31]. During the time flow of interest, the ICD coding systems changed, which might accept impaired comparability over time. The changes in ICD systems, definitions, and coding are less likely to affect the comparability of the aggregate diagnosis of SUID than of SIDS and other individual diagnoses.

Conclusions

The identification of country clusters in our study may promote inquiry into how changes of hazard factors such every bit smoking, immunisation, or other factors on the population level are related to SUID mortality. Of detail interest are comparisons of time trends between countries with a low - or intermediate - all-cause infant bloodshed, showing differential levels of SUID and SIDS mortality. While some data on the prevalence of take a chance factors may already exist available, more international collaboration is needed to appraise slumber environs and other take a chance factors in a standardized mode for comparison between countries. Compliance with definitions for SIDS and SUID/SUDI volition further increase the validity of international comparisons. Innovative methods of statistical analysis and data linkage may be of added value to generate new hypotheses for the prevention of sudden baby decease.

Availability of data and materials

The National Statistical Offices of the respective countries provided the information. In the case of missing data, we included additional information from the WHO Mortality Database if bachelor [18].

Abbreviations

- CDC:

-

Centers for Affliction Command and Prevention

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- German democratic republic :

-

German Autonomous Republic

- ICD:

-

International Classification of Deaths

- SIDS:

-

Sudden infant decease syndrome

- SUID :

-

Sudden unexpected infant expiry

- USSR:

-

Union of Soviet Socialist Republics

- WHO:

-

Earth Health Organisation

References

-

GBD 2015 Bloodshed and Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of decease, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the global burden of illness study 2015. Lancet. 2016;388(10053):1459–544.

-

Hauck FR, Tanabe KO. International trends in sudden infant expiry syndrome: stabilization of rates requires further action. Pediatrics. 2008;122(three):660–vi.

-

Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Drupe PJ, Evans Thousand, Fleming PJ. Major epidemiological changes in sudden infant expiry syndrome: a 20-year population-based study in the UK. Lancet. 2006;367(9507):314–9.

-

Muller-Nordhorn J, Hettler-Chen CM, Keil T, Muckelbauer R. Clan betwixt sudden infant death syndrome and diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis immunisation: an ecological study. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15:1.

-

Hogberg U, Bergstrom Eastward. Suffocated decumbent: the iatrogenic tragedy of SIDS. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(4):527–31.

-

Daltveit AK, Oyen N, Skjaerven R, Irgens LM. The epidemic of SIDS in Norway 1967-93: changing furnishings of take a chance factors. Arch Dis Child. 1997;77(ane):23–7.

-

Sawaguchi T, Namiki M. Recent trend of the incidence of sudden infant death syndrome in Japan. Early on Hum Dev. 2003;75(Suppl):S175–9.

-

Statistisches B. Gesundheits- und Sozialwesen in Übersichten (Teil IV), vol. Heft 27. Wiesbaden: Statistisches Bundesamt; 1995.

-

Gilbert R, Salanti G, Harden M, See S. Infant sleeping position and the sudden baby decease syndrome: systematic review of observational studies and historical review of recommendations from 1940 to 2002. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(4):874–87.

-

Colson ER, Rybin D, Smith LA, Colton T, Lister Grand, Corwin MJ. Trends and factors associated with babe sleeping position: the national infant sleep position study, 1993-2007. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163(12):1122–8.

-

Nelson EA, Taylor BJ. International child care practices report: infant sleep position and parental smoking. Early Hum Dev. 2001;64(1):vii–twenty.

-

Kinney HC, Thach BT. The sudden infant death syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(eight):795–805.

-

Moon RY, TASK FORCE ON SUDDEN INFANT Death SYNDROME. SIDS and Other Slumber-Related Infant Deaths: Evidence Base for 2016 Updated Recommendations for a Safe Infant Sleeping Surroundings. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20162940. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2940.

-

Taylor BJ, Garstang J, Engelberts A, Obonai T, Cote A, Freemantle J, Vennemann M, Healey One thousand, Sidebotham P, Mitchell EA, et al. International comparison of sudden unexpected death in infancy rates using a newly proposed set of cause-of-death codes. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(11):1018–23.

-

Goldstein RD, Blair PS, Sens MA, Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Krous HF, Rognum TO, Moon RY. Rd international congress on sudden I, kid D: inconsistent classification of unexplained sudden deaths in infants and children hinders surveillance, prevention and inquiry: recommendations from the third international congress on sudden infant and child decease. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2019;15(iv):622–8.

-

Malloy MH, MacDorman K. Changes in the classification of sudden unexpected infant deaths: Us, 1992-2001. Pediatrics. 2005;115(5):1247–53.

-

Shapiro-Mendoza CK, Tomashek KM, Anderson RN, Wingo J. Recent national trends in sudden, unexpected babe deaths: more show supporting a change in classification or reporting. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163(8):762–9.

-

WHO Mortality Database. Cause of Death Query Online. https://apps.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/mortality/causeofdeath_query/. Accessed 01 Sept 2017.

-

Anderson RN, Minino AM, Hoyert DL, Rosenberg HM. Comparability of cause of death betwixt ICD-9 and ICD-10: preliminary estimates. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2001;49(2):one–32.

-

Beckwith JB. Discussion of terminology and definition of the sudden infant expiry syndrome. In: Bergman AB, Beckwith JB, Ray CG, editors. Proceedings of the Second International Conference on Causes of Sudden Death in Infants. Seattle: University of Washington Press; 1970. p. fourteen–22.

-

Gangarosa EJ, Galazka AM, Wolfe CR, Phillips LM, Gangarosa RE, Miller E, Chen RT. Affect of anti-vaccine movements on pertussis control: the untold story. Lancet. 1998;351(9099):356–61.

-

Carvajal A, Caro-Paton T, Martin de Diego I, Martin Arias LH, Alvarez Requejo A, Lobato A. DTP vaccine and babe sudden death syndrome. Meta-assay. Med Clin (Barc). 1996;106(17):649–52.

-

Vennemann MM, Hoffgen One thousand, Bajanowski T, Hense HW, Mitchell EA. Do immunisations reduce the risk for SIDS? A meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2007;25(26):4875–nine.

-

Collaborators GBDT. Smoking prevalence and attributable disease brunt in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2015: a systematic assay from the global burden of disease report 2015. Lancet. 2017;389(10082):1885–906.

-

Case A, Paxson C. Parental beliefs and child health. Health Aff. 2002;21(2):164–78.

-

Willinger Yard, Hoffman HJ, Wu KT, Hou JR, Kessler RC, Ward SL, Keens TG, Corwin MJ. Factors associated with the transition to nonprone sleep positions of infants in the The states: the National Baby Sleep Position Written report. JAMA. 1998;280(4):329–35.

-

Byard RW, Lee V. A re-audit of the use of definitions of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) in peer-reviewed literature. J Forensic Legal Med. 2012;xix(8):455–6.

-

Krous HF, Beckwith JB, Byard RW, Rognum TO, Bajanowski T, Corey T, Cutz Due east, Hanzlick R, Keens TG, Mitchell EA. Sudden infant death syndrome and unclassified sudden baby deaths: a definitional and diagnostic approach. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):234–8.

-

Fleming PJ, Blair PS, Bacon C, Bensley D, Smith I, Taylor E, Berry J, Golding J, Tripp J. Environment of infants during sleep and take chances of the sudden babe death syndrome: results of 1993-5 case-command study for confidential enquiry into stillbirths and deaths in infancy. Confidential enquiry into stillbirths and deaths regional coordinators and researchers. BMJ. 1996;313(7051):191–5.

-

Carpenter RG, Irgens LM, Blair PS, England PD, Fleming P, Huber J, Jorch G, Schreuder P. Sudden unexplained infant death in 20 regions in Europe: case control study. Lancet. 2004;363(9404):185–91.

-

Eurostat. Health statistics – Atlas on mortality in the European Spousal relationship. Grand duchy of luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2009.

Acknowledgements

Nosotros are very grateful to the National Statistical Offices for providing the number of deaths in the respective ICD diagnostic categories and the number of live births per year.

Funding

Open up access funding provided past Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Affiliations

Contributions

JMN and SB conceptualized and designed the study, performed the initial analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and approved the final manuscript as submitted. AS, UG, and KN performed the analyses, reviewed and revised the manuscript. TK and SNW contributed to the pattern of the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the concluding manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Boosted information

Publisher'south Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Distribution of sudden unexpected baby death by its component diagnoses, according to land (1980, 1990, 2000); SIDS (ICD-10, R95), ill-divers and unknown causes of bloodshed (ICD-10, R96–99), accidental suffocation and strangulation in bed (ICD10, W75)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Artistic Eatables Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long every bit you lot give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and bespeak if changes were made. The images or other third party textile in this article are included in the commodity's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If fabric is not included in the commodity'southward Creative Commons licence and your intended use is non permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, yous will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and Permissions

About this commodity

Cite this article

Müller-Nordhorn, J., Schneider, A., Grittner, U. et al. International time trends in sudden unexpected babe death, 1969–2012. BMC Pediatr 20, 377 (2020). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12887-020-02271-x

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/ten.1186/s12887-020-02271-ten

Keywords

- Sudden unexpected baby death

- Sudden infant death syndrome

- Time trends

- Country-clusters

Source: https://bmcpediatr.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12887-020-02271-x

0 Response to "How Many Babies Died From Sids in 2018"

Post a Comment